Dive Into the Strange World of Jellyfish

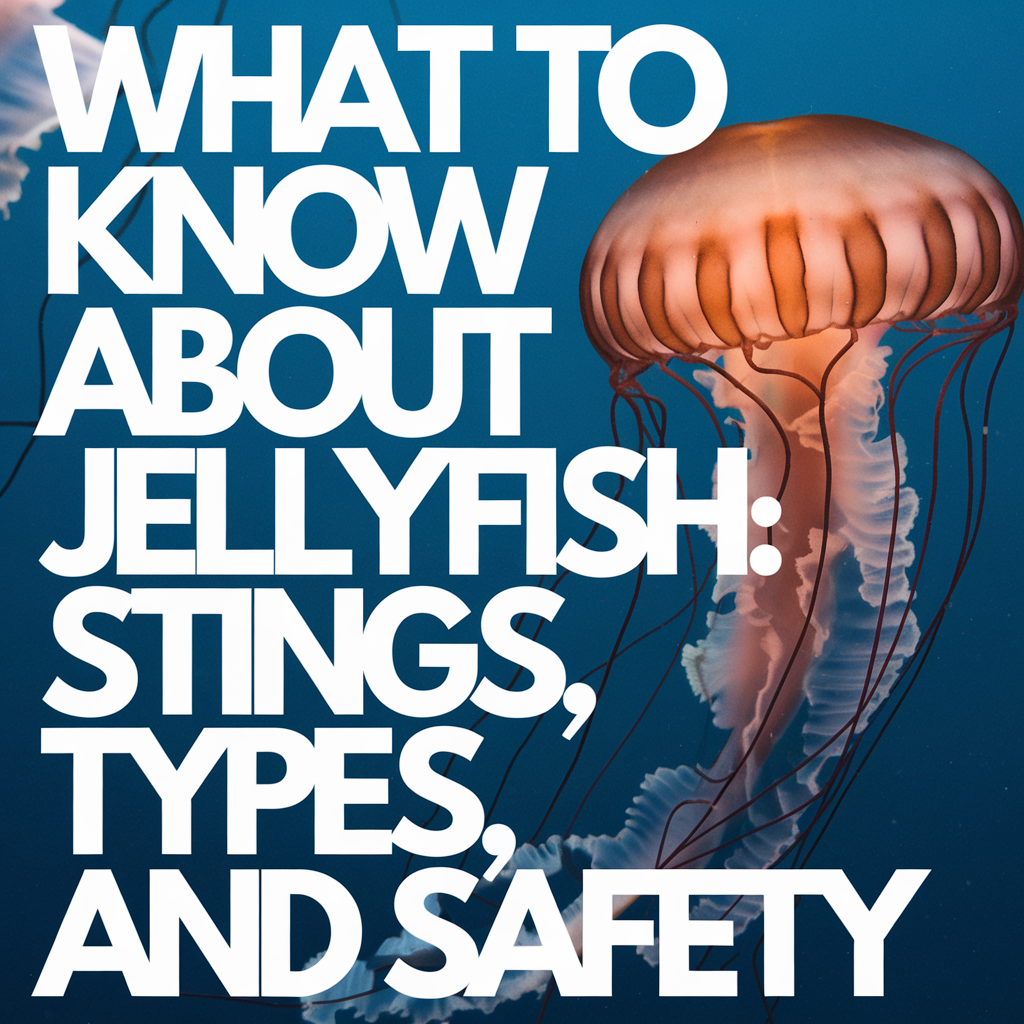

If you’ve ever stood ankle-deep in the surf and watched a translucent bell pulse by, you’ve met one of Earth’s oldest and strangest creatures. When people ask me what to know about jellyfish, I always start with this: they are not fish, they have no brain or bones, and yet they thrive in every ocean and even some lakes. Their story blends simple design with astonishing effectiveness—and once you understand how they work, you’ll never look at the ocean the same way again.

Quick Answers: What to Know About Jellyfish at a Glance

- They’re invertebrates called cnidarians, related to corals and sea anemones.

- They move by jet-propelling water from a bell-shaped body, but mostly drift with currents.

- Those stings? They come from spring-loaded cells called nematocysts.

- Life cycle includes tiny larvae, a polyp phase on hard surfaces, and a free-swimming medusa (the “jellyfish” you see).

- Some light up—bioluminescence is widespread and scientifically important.

- They’re older than dinosaurs and have survived multiple mass extinctions.

- Sea turtles (especially leatherbacks) love to eat them.

Anatomy 101: How a Jellyfish Works Without Brain, Blood, or Bones

One of the most surprising things to know about jellyfish is how simple their bodies are—and how well that simplicity works. A typical jellyfish has a gelatinous dome called the bell, tentacles, and often thicker “oral arms” that ferry food to a central mouth. Inside is a single gastrovascular cavity that digests food and circulates nutrients (no separate stomach and bloodstream here!).

Communication across the body happens through a net of nerve cells rather than a centralized brain. Many species have small sensory structures called rhopalia around the bell’s edge. These house balance organs (statocysts) and light sensors (ocelli); in box jellies, some of these are surprisingly sophisticated lens-bearing eyes. The bell’s rhythmic contractions push water behind them—simple jet propulsion that’s energy-efficient for drifting life.

That wobbling “body jelly” is called mesoglea—mostly water, with proteins that give structure. It makes jellies neutrally buoyant and beautifully translucent, nature’s version of ultralight engineering.

Life Cycle: From Tiny Planula to Drifting Medusa (and Sometimes Back Again)

Understanding the life cycle is core to what to know about jellyfish. Many species alternate between two forms. Adults (medusae) release eggs and sperm into the water. After fertilization, a microscopic larva called a planula settles onto a hard surface—pier pilings, oyster shells, rocky crevices—and becomes a stationary polyp.

That polyp can clone itself, bud new polyps, or undergo strobilation: stacking tiny saucer-like discs that pop off as baby medusae called ephyrae. These ephyrae grow into the recognizable, umbrella-shaped jellyfish. The polyp stage can last months to years, quietly biding time for the right conditions to unleash a “bloom.”

Nature adds some curveballs: the “immortal jellyfish” (Turritopsis dohrnii) can reverse the usual path and revert from medusa back to a polyp when stressed, essentially resetting its life cycle. It’s not invincible in the wild (predators and disease still take their toll), but the ability is real and astonishing.

Stings and Safety: What Really Helps and What Doesn’t

Here’s the part everyone asks about. The sting you feel comes from specialized cells (nematocysts) that fire like spring-loaded harpoons upon contact. They inject venom—usually to subdue tiny prey, not to harm you—but the human skin reaction can range from a mild tingle to severe pain, and in rare cases, systemic symptoms.

First aid basics to remember

- Get out of the water calmly to avoid more contact.

- Rinse the area with seawater. Freshwater can cause remaining stinging cells to discharge.

- If you know it’s a box jellyfish/Irukandji-type region, vinegar can help inactivate unfired nematocysts. Be aware: vinegar can worsen stings from Portuguese man o’ war (which is not a true jellyfish). If you’re unsure of the species, skip vinegar and stick with seawater rinse.

- Carefully remove visible tentacles with tweezers or a gloved hand, avoiding rubbing.

- Hot-water immersion (about 40–45°C/104–113°F) for 20–45 minutes can reduce pain and venom activity. If you don’t have a thermometer, use water that’s hot but not scalding.

- Seek medical help for severe pain, spreading rash, shortness of breath, chest tightness, nausea, or stings over large areas, the face, or in children.

What not to do

- Don’t rub sand or use a towel—it triggers more stings.

- Don’t use freshwater or ice right away.

- Don’t pee on it. That’s a persistent myth and can make things worse.

Lifeguards often know local species and protocols—if there’s a beach posting or flag system, follow it. That’s one of the smartest things to remember when thinking through what to know about jellyfish in your area.

Where They Live and Why Blooms Happen

Jellyfish occupy every ocean, from coastal lagoons to the deep sea, and even the Arctic and Antarctic. A few species, like the freshwater jelly Craspedacusta sowerbii, turn up in lakes on warm summer days. Globally, blooms (sudden surges in numbers) happen naturally, but human-caused factors can tip the scales: warmer waters, reduced predators from overfishing, nutrient pollution (which feeds zooplankton, the jellyfish buffet), and more artificial structures that give polyps places to live.

Blooms can affect tourism (beach closures), fisheries (jellies competing with fish larvae for food), and industry (clogging intake pipes at power plants). On the flip side, they’re food for many ocean creatures and part of a dynamic, ancient web.

Food Web Roles: Who Eats Whom in the Jellyfish Universe

Jellyfish are voracious predators of tiny drifting life: copepods, fish eggs, larvae, and even small fish. Some species, like upside-down jellies (Cassiopea), host photosynthetic microalgae in their tissues and get a share of sugar directly from sunlight, a clever survival strategy in sunlit shallows.

As for predators, sea turtles are the jelly specialists. If you’re curious about their incredible adaptations for this diet, dive into the world of leatherback turtles—gentle giants built to cruise long distances and gulp gelatinous prey with spiky esophageal papillae to keep slippery food moving down the hatch. You can also explore differences among turtle species—and why not all of them are jellyfish hunters—in loggerhead vs. green sea turtle.

Other jelly-eaters include the ocean sunfish (Mola), certain seabirds, and some fish. Top predators such as sharks rarely specialize on jellies but share the ecosystem with them and sometimes interact indirectly through food webs.

Glow and Wonder: Bioluminescence, GFP, and Science

Walk a dark beach in some places and you might see the sea sparkle. Jellyfish bioluminescence is part defense (startle your attacker), part communication, and endlessly captivating. One species, the hydromedusa Aequorea victoria, gifted science with green fluorescent protein (GFP)—a molecule that glows green under blue light. Scientists fused GFP to other proteins to watch cellular life in action, a breakthrough recognized with the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. It’s a perfect example of how learning what to know about jellyfish can ripple far beyond the shoreline.

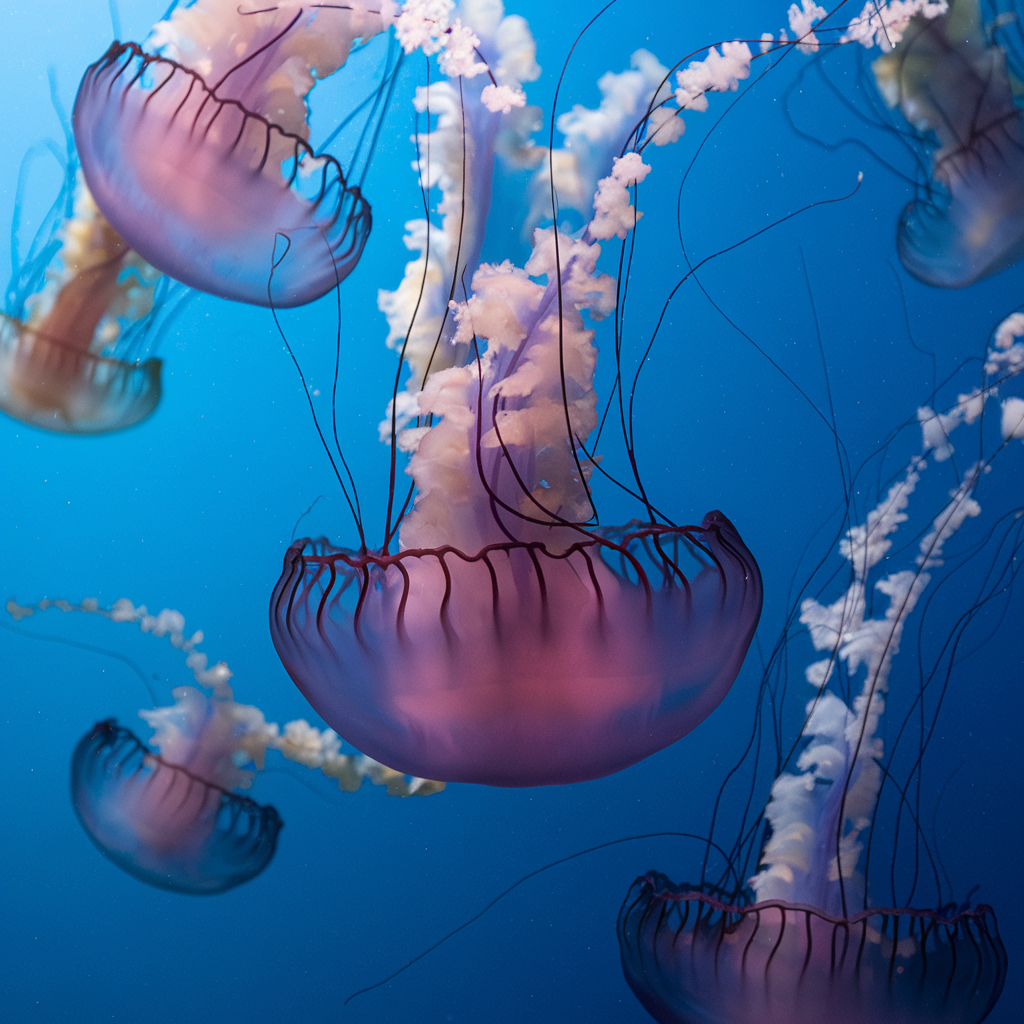

Sizes, Shapes, and Record-Holders

- Smallest: Tiny medusae barely a centimeter wide hover like living raindrops.

- Largest: The lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) can boast bells over 2 meters across and tentacles stretching past 30 meters.

- Most dangerous: Box jellies (cubozoans), including Chironex fleckeri, possess venom that can be life-threatening.

- Most surprising: The “immortal” Turritopsis dohrnii rewinds its life from adult to polyp stage.

Morphology varies: some jellyfish have fine hairlike tentacles; others sport thick oral arms for ferrying food. Colors can be subtle milky blues and purples or vivid oranges and reds, especially in deep-sea species.

Humans and Jellyfish: Cuisine, Culture, and Coastal Challenges

People in parts of Asia have eaten jellyfish for centuries, processing select species to remove water and firm their texture for salads and pickled dishes. Jellyfish collagen is studied for biomedical uses, and their blooms can be both a nuisance and a research opportunity.

On beaches, stings can cloud a perfect day; in industrial settings, mass aggregations sometimes clog intake pipes. Understanding what to know about jellyfish at a local level—seasonality, prevailing currents, and species—helps communities plan better beach safety and monitoring.

Conservation and Coexistence: Helping Sea Turtles and Healthy Seas

Many jellyfish predators are in trouble. Plastic bags and balloons can look like jellies underwater, a deadly trap for turtles. Cleaner seas and smarter waste practices help both turtles and jellyfish populations stay in balance. If you’re drawn to the species that rely on jellyfish, you’ll love our deeper dives into turtle species around the world and the remarkable lives of leatherbacks.

Curiosity leads to stewardship. The more we share accurate, practical knowledge—what to know about jellyfish, when and where to expect them, and how to react safely—the better our coasts will be for people and wildlife.

Traveler’s Tips: Beach-Ready Checklist for Jellyfish Season

- Check beach advisories and local social media from lifeguards before you go.

- Pack a small first-aid kit: tweezers, a small container for hot-water soaking or heat packs, and vinegar if you’re visiting regions with box jellies and you know the local guidance.

- Wear protective swimwear (long sleeves, leggings, or purpose-made “stinger suits”) during peak seasons.

- Avoid swimming in low light and after storms, when tentacles may drift inshore.

- Watch for jellies in the surf and on the strand line; even washed-up tentacles can sting.

- Swim where lifeguards are present and heed posted warnings.

Myths vs. Facts: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

- Myth: Jellyfish “attack” people. Fact: They’re drifters. Contact is usually accidental.

- Myth: All jellyfish are dangerous. Fact: Many stings are mild; a few species can be severe.

- Myth: Urine relieves stings. Fact: No. Use seawater rinse and hot-water immersion; vinegar only when species-appropriate.

- Myth: The Portuguese man o’ war is a jellyfish. Fact: It’s a siphonophore—a colony of specialized individuals acting as one.

- Myth: Jellyfish are “simple,” therefore unimportant. Fact: They shape food webs, fuel migrations, and even transformed cell biology research via GFP.

Species Spotlight: True Jellies, Box Jellies, and More

“Jellyfish” is a broad term. Here are the main groups you’ll meet when exploring what to know about jellyfish in detail:

- Scyphozoa (true jellyfish): Most classic beachcomber species, like moon jellies (Aurelia).

- Cubozoa (box jellies): Cube-shaped bells, potent venoms, and surprisingly complex eyes.

- Hydrozoa (hydromedusae): Often smaller; some produce tiny medusae; the man o’ war is in this wider group but is a siphonophore, not a single animal.

- Staurozoa (stalked jellies): Attached to the seafloor, looking like living flowers, especially in colder waters.

Depending on where you live, your local cast of characters may change with the seasons. In colder regions, lion’s mane jellies sometimes drift close to shore during spring and summer. In tropical Australia, box jellies and Irukandji are a well-known summertime hazard managed with stinger nets and public education.

How Climate and Coasts Influence Jellyfish

As oceans warm, jellyfish patterns can shift—earlier blooms, expanded ranges, or more successful polyp stages in certain areas. Nutrient runoff spurs plankton growth, which can feed larger jelly populations. Coastal infrastructure adds habitat for polyps to settle. Not every region will see the same changes, and some cycles are natural, but paying attention to local data and reports is part of smart coastal living.

If the polar seas fascinate you, remember that jellies cruise icy waters too—an underappreciated piece of Antarctic wildlife webs where gelatinous zooplankton overlap with krill and fish in complex seasonal patterns.

Jellyfish and You: Curiosity, Caution, and Respect

When readers ask me what to know about jellyfish before a beach vacation, I tell them: learn the local species, respect warning signs, and get excited to observe. Most jellyfish encounters are harmless, and watching a bell pulse through clear water is like seeing time slow down. Keep a bit of distance, snap that photo, and let the ocean’s living parachutes drift on.

And if jellyfish set you on a turtle kick (it happens!), don’t miss our deep dives into turtle species around the world and the incredible lives of leatherback turtles. For a broader overview of cnidarian cousins and other sea neighbors, browse our related ocean content on sharks and explore more of our jellyfish articles.

Keep Exploring the Ocean’s Drifters

There’s always more to learn, and that’s the best part. Knowing what to know about jellyfish—how they move, eat, glow, reproduce, and occasionally sting—turns a mystery into a living, breathing (well, pulsing) story. Whether you’re beachcombing with kids, snorkeling a reef, or simply daydreaming about the sea, jellyfish are a perfect reminder that evolution’s simplest designs can be the most enduringly elegant.